My Christmas tree is out at the curb, which means it’s time to start planning 2018 travels. This year, I hope to visit some big-name destinations — maybe Madrid, maybe Amsterdam, maybe Prague? But as I reflect on recent trips, I’m struck by how many favorite travel memories have taken place in Europe’s underappreciated corners. As your travel dreams take shape for 2018, consider peppering your itinerary with a few off-the-beaten-path discoveries — the sorts of places that Rick Steves, decades ago, dubbed “Back Doors.” Here are 10 of my current favorites.

Lake Mývatn Area, Iceland

Driving around the perimeter of Iceland on the 800-mile Ring Road this summer (working on our upcoming Rick Steves Iceland guidebook), I binged on an unceasing stream of cinematic landscapes. But what sticks with me most vividly is the region surrounding Lake Mývatn, a geological hotspot that straddles the European and North American tectonic plates. Birds love this dreamy lake, as do the swarms of microscopic midges (for whom the lake is named) that invade the nostrils and mouths of summertime visitors. But the bugs are easy enough to ignore as you explore the lakeshore’s volcanic terrain — from the “pseudocraters” (gigantic burst bubbles of molten rock) at Skútustaðir, to the forest of jagged lava pillars at Dimmuborgir, to the climbable volcanic cone at Hverfjall. And the thermal fun crescendos just to the east: the delightful Mývatn Thermal Baths (the lowbrow, half-price alternative to the famous Blue Lagoon), the volcanic valley at Kralfa (with a steaming geothermal power plant), and the bubbling, hissing field at Námafjall (pictured above). Stepping out of my car at Námafjall, I plugged my nose against the suffocating sulfur vapors and wandered, slack-jawed, across an otherworldly landscape of vivid-yellow sands, bubbling gray ponds, and piles of rocks steaming like furious teakettles. Many visitors drop into Iceland for just a few days, and stick close to Reykjavik — which is a good plan, if you’re in a rush. But the opportunity to linger in Mývatn (about a six-hour drive from Reykjavík) may be reason enough to extend your trip by a few days…and turn your stopover into a full-blown road trip.

Driving around the perimeter of Iceland on the 800-mile Ring Road this summer (working on our upcoming Rick Steves Iceland guidebook), I binged on an unceasing stream of cinematic landscapes. But what sticks with me most vividly is the region surrounding Lake Mývatn, a geological hotspot that straddles the European and North American tectonic plates. Birds love this dreamy lake, as do the swarms of microscopic midges (for whom the lake is named) that invade the nostrils and mouths of summertime visitors. But the bugs are easy enough to ignore as you explore the lakeshore’s volcanic terrain — from the “pseudocraters” (gigantic burst bubbles of molten rock) at Skútustaðir, to the forest of jagged lava pillars at Dimmuborgir, to the climbable volcanic cone at Hverfjall. And the thermal fun crescendos just to the east: the delightful Mývatn Thermal Baths (the lowbrow, half-price alternative to the famous Blue Lagoon), the volcanic valley at Kralfa (with a steaming geothermal power plant), and the bubbling, hissing field at Námafjall (pictured above). Stepping out of my car at Námafjall, I plugged my nose against the suffocating sulfur vapors and wandered, slack-jawed, across an otherworldly landscape of vivid-yellow sands, bubbling gray ponds, and piles of rocks steaming like furious teakettles. Many visitors drop into Iceland for just a few days, and stick close to Reykjavik — which is a good plan, if you’re in a rush. But the opportunity to linger in Mývatn (about a six-hour drive from Reykjavík) may be reason enough to extend your trip by a few days…and turn your stopover into a full-blown road trip.

Sarlat Market Day, Dordogne, France

Of all the delightful activities I’ve enjoyed in France, my favorite remains the lazy Saturday morning I spent wandering the market stalls in the town of Sarlat. Rickety tables groaned with oversized wheels of mountain cheese, tidy little stacks of salamis, cans of foie gras and duck confit, and a cornucopia of fresh produce. Market day in rural and small-town France isn’t just a chance to stock up — it’s a social institution, where neighbors mix and mingle, and where consumers forge lasting relationships with their favorite producers. And when the market wraps up, even before the sales kiosks are folded up and stowed, al fresco café tables overflow with weary shoppers catching up with their friends. While Sarlat is my favorite market (and my favorite little town in France), you can have a similar experience anywhere in the country; I’ve also enjoyed memorable market days in Uzès (Provence), Beaune (Burgundy), St-Jean-de-Luz (Basque Country), and even in Paris. Just research the local jour de marché schedule, wherever you’re going in France, and make time for one or two. And when you get there…. Actually. Slow. Down. Throw away your itinerary for a morning. Become a French villager with an affinity for quality ingredients. Browse the goods. Get picky. And assemble the French picnic of your dreams.

Of all the delightful activities I’ve enjoyed in France, my favorite remains the lazy Saturday morning I spent wandering the market stalls in the town of Sarlat. Rickety tables groaned with oversized wheels of mountain cheese, tidy little stacks of salamis, cans of foie gras and duck confit, and a cornucopia of fresh produce. Market day in rural and small-town France isn’t just a chance to stock up — it’s a social institution, where neighbors mix and mingle, and where consumers forge lasting relationships with their favorite producers. And when the market wraps up, even before the sales kiosks are folded up and stowed, al fresco café tables overflow with weary shoppers catching up with their friends. While Sarlat is my favorite market (and my favorite little town in France), you can have a similar experience anywhere in the country; I’ve also enjoyed memorable market days in Uzès (Provence), Beaune (Burgundy), St-Jean-de-Luz (Basque Country), and even in Paris. Just research the local jour de marché schedule, wherever you’re going in France, and make time for one or two. And when you get there…. Actually. Slow. Down. Throw away your itinerary for a morning. Become a French villager with an affinity for quality ingredients. Browse the goods. Get picky. And assemble the French picnic of your dreams.

Ruin Pubs, Budapest, Hungary

I must admit, I’m not really a “nightlife guy.” But when I’m in Budapest, I budget extra time to simply wander the lively streets of the Seventh District — just behind the Great Synagogue, in the heart of the city — and drop into a variety of “ruin pubs.” A ruin pub is a uniquely Budapest invention (though these days, it’s been copied by hipster entrepreneurs everywhere): Find a ramshackle, crumbling, borderline-condemned old building. Fill its courtyard with mismatched furniture and twinkle lights. And serve up a fun variety of drinks, from basic beers to twee cocktails to communist-kitsch sodas for nostalgic fortysomethings. The Seventh District — the former Jewish Quarter, and for decades a wasteland of dilapidated townhouses — gave root to ruin pubs several years back. And today, tucked between the synagogues and kosher shops are dozens of ruin pubs, each one with its own personality. While you could link up a variety of the big-name ruin pubs (and my self-guided “Ruin Pub Crawl” in the Rick Steves Budapest guidebook does exactly that), the best plan may simply be to explore Kazinczy street and find the place that suits your mood.

I must admit, I’m not really a “nightlife guy.” But when I’m in Budapest, I budget extra time to simply wander the lively streets of the Seventh District — just behind the Great Synagogue, in the heart of the city — and drop into a variety of “ruin pubs.” A ruin pub is a uniquely Budapest invention (though these days, it’s been copied by hipster entrepreneurs everywhere): Find a ramshackle, crumbling, borderline-condemned old building. Fill its courtyard with mismatched furniture and twinkle lights. And serve up a fun variety of drinks, from basic beers to twee cocktails to communist-kitsch sodas for nostalgic fortysomethings. The Seventh District — the former Jewish Quarter, and for decades a wasteland of dilapidated townhouses — gave root to ruin pubs several years back. And today, tucked between the synagogues and kosher shops are dozens of ruin pubs, each one with its own personality. While you could link up a variety of the big-name ruin pubs (and my self-guided “Ruin Pub Crawl” in the Rick Steves Budapest guidebook does exactly that), the best plan may simply be to explore Kazinczy street and find the place that suits your mood.

Julian Alps, Slovenia

This gorgeous corner of my favorite country has always been high on my personal “must list.” It’s a little slice of heaven: Cut-glass alpine peaks tower over fine little Baroque-steepled towns, all laced together by an eerily turquoise river. While this place should be overrun with crowds, on my latest visit — in late September — I had the place nearly to myself. A few A+ travelers have begun to find their way to the “sunny side of the Alps”: Rafters, kayakers, and adventure sports fanatics are drawn to the sparkling waters of the Soča River. Historians peruse the well-curated array of outdoor museums and cemeteries from World War I’s Isonzo Front, where Ernest Hemingway famously drove an ambulance. Skiers gape up at the 660-foot-tall jump at Planica, home to the world championships of ski flying (for daredevils who consider ski jumping for wimps). And foodies make a pilgrimage to Hiša Franko, the world-class restaurant of Ana Roš — a self-trained Slovenian chef who was profiled on Netflix’s Chef’s Table, and was named the World’s Best Female Chef 2017. (I recently enjoyed a fantastic dinner at Hiša Franko, and was tickled to be greeted by Ana herself, who took my coat and showed me to my table.) As a bonus, the Julian Alps pair perfectly with a visit to northern Italy: On my latest trip, I spent the morning hiking on alpine trails and exploring antique WWI trenches carved into the limestone cliffs, had lunch immersed in the pastoral beauty of Slovenia’s Goriška Brda wine region (also egregiously overlooked), then hopped on the freeway and was cruising the canals of Venice well before dinnertime.

This gorgeous corner of my favorite country has always been high on my personal “must list.” It’s a little slice of heaven: Cut-glass alpine peaks tower over fine little Baroque-steepled towns, all laced together by an eerily turquoise river. While this place should be overrun with crowds, on my latest visit — in late September — I had the place nearly to myself. A few A+ travelers have begun to find their way to the “sunny side of the Alps”: Rafters, kayakers, and adventure sports fanatics are drawn to the sparkling waters of the Soča River. Historians peruse the well-curated array of outdoor museums and cemeteries from World War I’s Isonzo Front, where Ernest Hemingway famously drove an ambulance. Skiers gape up at the 660-foot-tall jump at Planica, home to the world championships of ski flying (for daredevils who consider ski jumping for wimps). And foodies make a pilgrimage to Hiša Franko, the world-class restaurant of Ana Roš — a self-trained Slovenian chef who was profiled on Netflix’s Chef’s Table, and was named the World’s Best Female Chef 2017. (I recently enjoyed a fantastic dinner at Hiša Franko, and was tickled to be greeted by Ana herself, who took my coat and showed me to my table.) As a bonus, the Julian Alps pair perfectly with a visit to northern Italy: On my latest trip, I spent the morning hiking on alpine trails and exploring antique WWI trenches carved into the limestone cliffs, had lunch immersed in the pastoral beauty of Slovenia’s Goriška Brda wine region (also egregiously overlooked), then hopped on the freeway and was cruising the canals of Venice well before dinnertime.

Vigeland Park, Oslo, Norway

My favorite piece of art in Europe isn’t a painting, and it isn’t in a museum. It’s a park — a grassy canvas where a single artist, the early-20th-century sculptor Gustav Vigeland, was given carte blanche to design and decorate as he saw fit. The city of Oslo gave Vigeland a big studio, and turned him loose in the adjoining park for 20 years. He filled that space with a sprawling yet harmonious ensemble of 600 bronze and granite figures, representing every emotion and rite of passage in the human experience, all frozen in silent conversation with each other — and with the steady stream of Oslo urbanites and tourists who flow through Vigeland’s masterpiece. The naked figures (which might provoke giggles among prudish Americans) reinforce the sense of timelessness and universality: They belong not to any one time or place, but to every time and every place — from Adam and Eve to contemporary Norway. Over the last decade and a half, I’ve been to Vigeland Park three times. Each time, I was in a totally different state of mind. And each time, the statues spoke to me like old friends — sometimes with the same old message, and sometimes with new insights. With all due respect to da Vinci, Van Gogh, and Picasso, no single artistic experience in Europe is more meaningful or impactful to me than Vigeland Park.

My favorite piece of art in Europe isn’t a painting, and it isn’t in a museum. It’s a park — a grassy canvas where a single artist, the early-20th-century sculptor Gustav Vigeland, was given carte blanche to design and decorate as he saw fit. The city of Oslo gave Vigeland a big studio, and turned him loose in the adjoining park for 20 years. He filled that space with a sprawling yet harmonious ensemble of 600 bronze and granite figures, representing every emotion and rite of passage in the human experience, all frozen in silent conversation with each other — and with the steady stream of Oslo urbanites and tourists who flow through Vigeland’s masterpiece. The naked figures (which might provoke giggles among prudish Americans) reinforce the sense of timelessness and universality: They belong not to any one time or place, but to every time and every place — from Adam and Eve to contemporary Norway. Over the last decade and a half, I’ve been to Vigeland Park three times. Each time, I was in a totally different state of mind. And each time, the statues spoke to me like old friends — sometimes with the same old message, and sometimes with new insights. With all due respect to da Vinci, Van Gogh, and Picasso, no single artistic experience in Europe is more meaningful or impactful to me than Vigeland Park.

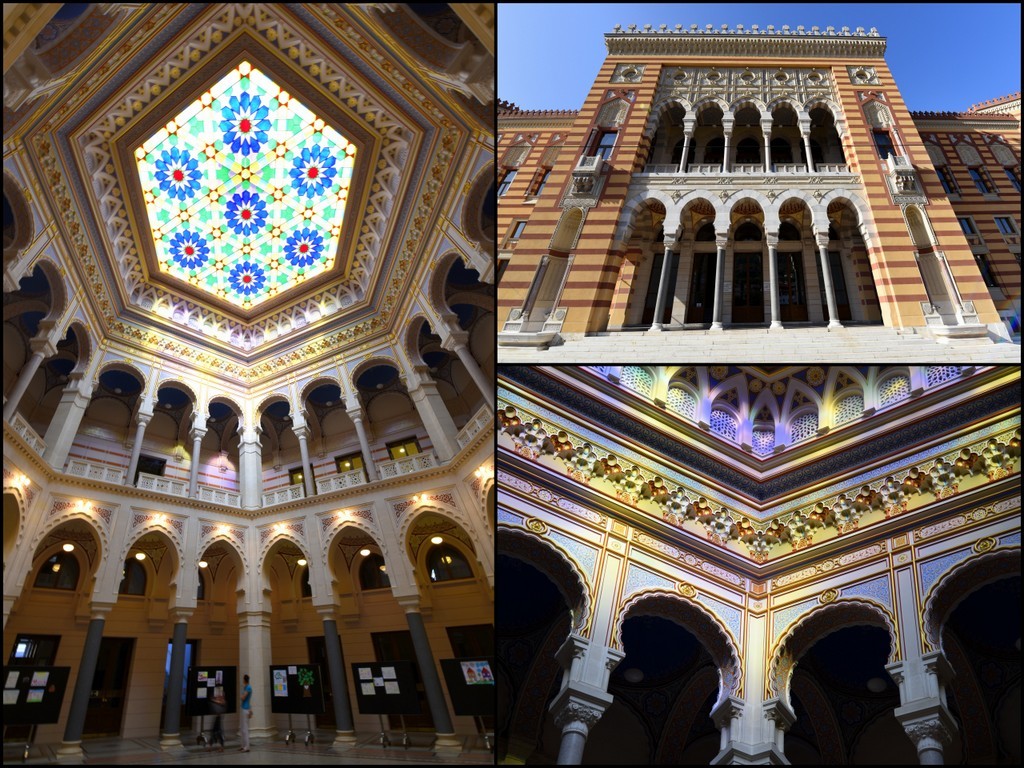

Sarajevo, Bosnia-Herzegovina

Sarači #16 is the most interesting address in downtown Sarajevo. Facing east — toward the Ottoman-era old town, Baščaršija — you’re transported to medieval Turkey: a bustling bazaar with slate-roofed houses, chunky river-stone cobbles, the tap-tap-tap of coppersmiths’ hammers, and a pungent haze of hookah smoke and grilled meats. Then, turning to the west, you’re peering down Ferhadija, the main thoroughfare of Habsburg Sarajevo. This could be a Vienna suburb, where stern, genteel Baroque facades look down over cafés teeming with urbanites. Within a few short blocks of this spot stand the city’s historic synagogue, its oldest Serbian Orthodox church, its Catholic cathedral, and its showcase mosque. Few places on earth are so layered with history. And then there’s the latest chapter: the poignant story of the Siege of Sarajevo in the mid-1990s, when the town was surrounded by snipers for more than 1,400 days — connected to the outside world only by a muck-filled tunnel and a steep mountain ascent. Proud Sarajevans you’ll meet are often willing, or even eager, to share their stories of living a horrific reality that we experienced only through the Nightly News. And if you’re lucky, they’ll invite you for a cup of Bosnian coffee — and explain why it’s integral to their worldview and their social life. Many travelers do a strategic side-trip from Croatia to the town of Mostar — a good first taste of Bosnia, but what I consider “Bosnia with training wheels.” But for the full Bosnian experience, I’d invest another day or two and delve a couple of hours deeper into the country…to Sarajevo.

Sarači #16 is the most interesting address in downtown Sarajevo. Facing east — toward the Ottoman-era old town, Baščaršija — you’re transported to medieval Turkey: a bustling bazaar with slate-roofed houses, chunky river-stone cobbles, the tap-tap-tap of coppersmiths’ hammers, and a pungent haze of hookah smoke and grilled meats. Then, turning to the west, you’re peering down Ferhadija, the main thoroughfare of Habsburg Sarajevo. This could be a Vienna suburb, where stern, genteel Baroque facades look down over cafés teeming with urbanites. Within a few short blocks of this spot stand the city’s historic synagogue, its oldest Serbian Orthodox church, its Catholic cathedral, and its showcase mosque. Few places on earth are so layered with history. And then there’s the latest chapter: the poignant story of the Siege of Sarajevo in the mid-1990s, when the town was surrounded by snipers for more than 1,400 days — connected to the outside world only by a muck-filled tunnel and a steep mountain ascent. Proud Sarajevans you’ll meet are often willing, or even eager, to share their stories of living a horrific reality that we experienced only through the Nightly News. And if you’re lucky, they’ll invite you for a cup of Bosnian coffee — and explain why it’s integral to their worldview and their social life. Many travelers do a strategic side-trip from Croatia to the town of Mostar — a good first taste of Bosnia, but what I consider “Bosnia with training wheels.” But for the full Bosnian experience, I’d invest another day or two and delve a couple of hours deeper into the country…to Sarajevo.

Val d’Orcia, Tuscany, Italy

Of all of Tuscany’s appealing corners, the Val d’Orcia (“val dor-chah”) is — for me — the most enchanting. While just a short drive from the tourist throngs in Florence, San Gimignano, Siena, or the Chianti region, the Val d’Orcia — bookended by the charming towns of Montepulciano and Montalcino (both synonymous with fine Tuscan wine) — feels like a peaceful, overlooked eddy of rural life. This strip of land is where most of the iconic “Tuscany scenery” photographs are taken: Winding, cypress-lined driveways; vibrant-green, rolling farm fields that look like a circa-2000 screensaver; and lonely chapels perched on verdant ridges. And it’s the backdrop for famous scenes in everything from The English Patient to Gladiator to Master of None. And yet, the area has no “major sights” — no sculptures by Michelangelo, no paintings by da Vinci, no leaning towers — which, mercifully, keeps it just beyond the itineraries of whistle-stop, bucket-list tourists. I have savored several visits — including a particularly memorable Thanksgiving week with family — settling into my favorite agriturismo, Cretaiole, in the heart of the Val d’Orica. And every moment of every trip lives on as a mental postcard: Making fresh pasta. Sawing into a deliciously rare slab of Chianina beef T-bone. Following a truffle-hunting dog as it sniffs its way through an oak forest. And on and on. If you have a day to spare between Rome and Florence, don’t go to the Val d’Orcia. But if you have several days to really delve into the best of Tuscany…let’s talk.

Of all of Tuscany’s appealing corners, the Val d’Orcia (“val dor-chah”) is — for me — the most enchanting. While just a short drive from the tourist throngs in Florence, San Gimignano, Siena, or the Chianti region, the Val d’Orcia — bookended by the charming towns of Montepulciano and Montalcino (both synonymous with fine Tuscan wine) — feels like a peaceful, overlooked eddy of rural life. This strip of land is where most of the iconic “Tuscany scenery” photographs are taken: Winding, cypress-lined driveways; vibrant-green, rolling farm fields that look like a circa-2000 screensaver; and lonely chapels perched on verdant ridges. And it’s the backdrop for famous scenes in everything from The English Patient to Gladiator to Master of None. And yet, the area has no “major sights” — no sculptures by Michelangelo, no paintings by da Vinci, no leaning towers — which, mercifully, keeps it just beyond the itineraries of whistle-stop, bucket-list tourists. I have savored several visits — including a particularly memorable Thanksgiving week with family — settling into my favorite agriturismo, Cretaiole, in the heart of the Val d’Orica. And every moment of every trip lives on as a mental postcard: Making fresh pasta. Sawing into a deliciously rare slab of Chianina beef T-bone. Following a truffle-hunting dog as it sniffs its way through an oak forest. And on and on. If you have a day to spare between Rome and Florence, don’t go to the Val d’Orcia. But if you have several days to really delve into the best of Tuscany…let’s talk.

Psyrri Neighborhood, Athens, Greece

A few years removed from the depths of its economic crisis, Athens has re-emerged as a red-hot destination. Revisiting the city a few months ago, I was struck by how many tourists I saw — and by how many of them refused to venture beyond the cutesy, crowded Plaka zone that rings the base of the Acropolis. And that’s a shame, because literally across the street from the Plaka’s central square, Monastiraki, is one of Athens’ most colorful and fun-to-explore neighborhoods: Psyrri (“psee-ree”). Not long ago, this was a deserted and dangerous slum. But recently, Psyrri has emerged as a trendy dining and nightlife zone. Its graffiti-slathered apartment blocks now blossom with freshly remodeled Airbnb rentals. This still-gritty area may feel a little foreboding at first, but if you can get past the street art, grime, and motorbikes parked on potholed sidewalks, it’s easy to enjoy the hipster soul of the neighborhood that’s leading many to dub Athens “The New Berlin.” For the upcoming fifth edition of our Rick Steves Greece guidebook, Psyrri inspired me to write a brand-new, food-and-street-art-themed self-guided walk chapter. In just a few blocks, between the Plaka and the thriving Central Market, you can stop in for nibbles and sips of sesame-encrusted dough rings (koulouri), delicate phyllo-custard pastry (bougatsa), deep-fried donuts (loukoumades), anise-flavored ouzo liquor, and unfiltered “Greek coffee.” If you’re going to Athens, break free of the Plaka rut, walk five minutes away from the hovering Parthenon, and sample this accessible, authentic slice of urban Greek life.

A few years removed from the depths of its economic crisis, Athens has re-emerged as a red-hot destination. Revisiting the city a few months ago, I was struck by how many tourists I saw — and by how many of them refused to venture beyond the cutesy, crowded Plaka zone that rings the base of the Acropolis. And that’s a shame, because literally across the street from the Plaka’s central square, Monastiraki, is one of Athens’ most colorful and fun-to-explore neighborhoods: Psyrri (“psee-ree”). Not long ago, this was a deserted and dangerous slum. But recently, Psyrri has emerged as a trendy dining and nightlife zone. Its graffiti-slathered apartment blocks now blossom with freshly remodeled Airbnb rentals. This still-gritty area may feel a little foreboding at first, but if you can get past the street art, grime, and motorbikes parked on potholed sidewalks, it’s easy to enjoy the hipster soul of the neighborhood that’s leading many to dub Athens “The New Berlin.” For the upcoming fifth edition of our Rick Steves Greece guidebook, Psyrri inspired me to write a brand-new, food-and-street-art-themed self-guided walk chapter. In just a few blocks, between the Plaka and the thriving Central Market, you can stop in for nibbles and sips of sesame-encrusted dough rings (koulouri), delicate phyllo-custard pastry (bougatsa), deep-fried donuts (loukoumades), anise-flavored ouzo liquor, and unfiltered “Greek coffee.” If you’re going to Athens, break free of the Plaka rut, walk five minutes away from the hovering Parthenon, and sample this accessible, authentic slice of urban Greek life.

Moscow, Russia

On my last visit to Moscow, in the summer of 2014, Russia was in the news: military action in Crimea and eastern Ukraine, Putin’s brutal crackdown on homosexuality and punk-rock protesters Pussy Riot, and the recently completed Sochi Olympics. Of course, since then, the headlines have changed, but Russia is in the news more than ever. That’s why I consider Moscow to be Europe’s most fascinating — and challenging — destination. People back home shake their heads and wonder: How can these people support Putin, who (to us) is so clearly a demagogue? I take that not as a rhetorical question, but as a genuine one that deserves a real answer. And a thoughtful visit to Moscow — even “just” as a casual tourist — can offer some insights. Designed-to-intimidate Red Square and the Kremlin fill onlookers with awe and respect. The still-standing headstone of Josef Stalin — tucked along the Kremlin Wall, just behind Lenin’s Tomb and its waxy occupant — seems to suggest that the Russian appetite for absolute rulers is nothing new. But mostly, I’m struck by the improvements I see in Moscow with each return visit. On my first trip, in the early 2000s, the famous Gorky Park was a ramshackle, potholed mess, and the Cathedral of Christ the Savior — which had been demolished by communist authorities — was still being rebuilt. But today, Gorky Park is a lush, pristine, manicured people zone, and the sunshine glitters off the cathedral’s rebuilt golden dome. Just up the river, a Shanghai-style forest of futuristic skyscrapers rises up from a onetime industrial wasteland. In short, the Russian capital — which has always been interesting — is now actually a pleasant place to travel. Finding myself really enjoying Moscow, for the first time, makes it easier to imagine how many Russians might be convinced that Putin is Making Russia Great Again.

On my last visit to Moscow, in the summer of 2014, Russia was in the news: military action in Crimea and eastern Ukraine, Putin’s brutal crackdown on homosexuality and punk-rock protesters Pussy Riot, and the recently completed Sochi Olympics. Of course, since then, the headlines have changed, but Russia is in the news more than ever. That’s why I consider Moscow to be Europe’s most fascinating — and challenging — destination. People back home shake their heads and wonder: How can these people support Putin, who (to us) is so clearly a demagogue? I take that not as a rhetorical question, but as a genuine one that deserves a real answer. And a thoughtful visit to Moscow — even “just” as a casual tourist — can offer some insights. Designed-to-intimidate Red Square and the Kremlin fill onlookers with awe and respect. The still-standing headstone of Josef Stalin — tucked along the Kremlin Wall, just behind Lenin’s Tomb and its waxy occupant — seems to suggest that the Russian appetite for absolute rulers is nothing new. But mostly, I’m struck by the improvements I see in Moscow with each return visit. On my first trip, in the early 2000s, the famous Gorky Park was a ramshackle, potholed mess, and the Cathedral of Christ the Savior — which had been demolished by communist authorities — was still being rebuilt. But today, Gorky Park is a lush, pristine, manicured people zone, and the sunshine glitters off the cathedral’s rebuilt golden dome. Just up the river, a Shanghai-style forest of futuristic skyscrapers rises up from a onetime industrial wasteland. In short, the Russian capital — which has always been interesting — is now actually a pleasant place to travel. Finding myself really enjoying Moscow, for the first time, makes it easier to imagine how many Russians might be convinced that Putin is Making Russia Great Again.

Orkney Islands, Scotland

I traveled all over Scotland a couple of summers ago, working on the Rick Steves Scotland guidebook. And the most intriguing place I visited had nothing to do with kilts, bagpipes, or moody glens: the archipelago of Orkney, barely visible from Britain’s northernmost point at John o’ Groats. This flat, mossy island feels far from what I think of as “Scotland.” For most of its history, it was a Norse trading outpost, rather than a clan stronghold. And today it remains a world apart. Five-thousand-year-old stone circles and rows point the way to prehistoric subterranean settlements. The main town, Kirkwall, has a quirky tradition for a no-holds-barred, town-wide annual rugby match, and a fascinating-to-tour church. And you can still drive across the “Churchill Barriers,” installed by Sir Winston after a Nazi U-Boat snuck into the famous harbor called Scapa Flow and blew up a British warship. But my favorite sight is the Italian Chapel: a drab wartime hut transformed into a delicate, ethereal Catholic chapel by Italian POWs who were allowed to improvise the decor from whatever materials they could scavenge. While Orkney takes some effort to reach, it’s worthwhile for the unique and captivating sightseeing it affords. (To get the most out of your time on Orkney, book a tour with Kinlay at Orkney Uncovered.)

I traveled all over Scotland a couple of summers ago, working on the Rick Steves Scotland guidebook. And the most intriguing place I visited had nothing to do with kilts, bagpipes, or moody glens: the archipelago of Orkney, barely visible from Britain’s northernmost point at John o’ Groats. This flat, mossy island feels far from what I think of as “Scotland.” For most of its history, it was a Norse trading outpost, rather than a clan stronghold. And today it remains a world apart. Five-thousand-year-old stone circles and rows point the way to prehistoric subterranean settlements. The main town, Kirkwall, has a quirky tradition for a no-holds-barred, town-wide annual rugby match, and a fascinating-to-tour church. And you can still drive across the “Churchill Barriers,” installed by Sir Winston after a Nazi U-Boat snuck into the famous harbor called Scapa Flow and blew up a British warship. But my favorite sight is the Italian Chapel: a drab wartime hut transformed into a delicate, ethereal Catholic chapel by Italian POWs who were allowed to improvise the decor from whatever materials they could scavenge. While Orkney takes some effort to reach, it’s worthwhile for the unique and captivating sightseeing it affords. (To get the most out of your time on Orkney, book a tour with Kinlay at Orkney Uncovered.)

Where are you headed in 2018?

Right in front of me, two families bump into each other and spend several minutes catching up. Their awkward pre-teen, with his akimbo haircut and high-waisted mom jeans, yawns and fidgets. At the next table, tourists from Saudi Arabia — probably feeling more at home here than anywhere else in Europe — laugh the unbridled, relaxed laughter that only a vacation can bring. And all around, people are simply enjoying one of Europe’s most underrated cities. They’re in on the secret. And I’m so glad to be, too.

Right in front of me, two families bump into each other and spend several minutes catching up. Their awkward pre-teen, with his akimbo haircut and high-waisted mom jeans, yawns and fidgets. At the next table, tourists from Saudi Arabia — probably feeling more at home here than anywhere else in Europe — laugh the unbridled, relaxed laughter that only a vacation can bring. And all around, people are simply enjoying one of Europe’s most underrated cities. They’re in on the secret. And I’m so glad to be, too.