Studying abroad can be a life-changing opportunity for any student. It certainly was for me. The first time I ever set foot in Europe was when I arrived in Spain to spend the next three and a half months in the historic university city of Salamanca. I recently returned to Salamanca (for the first time in 22 years!), and I found myself mentally replaying one of my favorite experiences from that trip — one that got this bumpkin from Ohio thinking in a whole new way about the beautiful and often surprising interplay of culture and food.

Midway through my semester abroad in Salamanca, on a drizzly Saturday morning in November of 1996, my host family announced at breakfast: “Moisés, today we’re going to la granja!”

Moisés — my middle name — is what I go by in Spanish (because “Cameron” is perilously close to camarón — “shrimp”). And la granja was, it turns out, the family farm. The idea that my host family owned a countryside property was hard to fathom. Shoehorned into a tight, seventh-floor apartment in the urban jungle of Salamanca, they seemed pure urbanites. Piling in the family car — and jamming three of us in the tiny backseat — they explained that la granja was a family property, going back generations.

When you leave Salamanca, there’s no sprawl. It’s just ten-story concrete apartment blocks one minute…and then, abruptly, the endless and lonesome expanse of the Castilian Plain the next. After about an hour driving through sun-parched husks of humble crops, we pulled up a gravel driveway to a time-passed farmstead.

My host brother, Fran, took me on a walk around the grounds. Leaves crunching beneath our feet, we passed through an oak grove. Fran rustled around in the crinkly leaves and pulled out an acorn.

“Ah, bellota!” he said with pride. “The bellota is so important to this part of Spain. We feed bellotas to the very best jamón — jamón iberico de bellota.” Spaniards are aficionados of their air-cured prosciutto — jamón. And even in my brief stay in the country, I’d already learned that jamón iberico de bellota was the connoisseur’s choice: made from black-footed pigs, freely roaming the forests of western Spain, and feasting on a diet of top-quality acorns.

“The bellota is perfect nutrition,” Fran continued. “Even people even eat it!” Noticing my failure to hide my disgust, Fran took a big, toothy bite of the acorn, finally managing to sever, chew, and swallow a tough little chunk. “Delicioso,” he said through a wince. He offered me a bite. Gamely, I bit into the nut, which flooded my mouth with an astringent cocktail of intense bitter and sour. All I could muster, through clenched teeth, was, “Sí, fuerte!”

Heading back toward the farmhouse, we passed a bin full of corn cobs. “Do you ever eat this?” I asked. Fran grimaced and laughed a little bit. “Corn? Of course we don’t eat corn. That’s animal feed!” He shook his head and muttered to himself again, “Corn…” Having grown up in Central Ohio — with its sultry summers producing towering stalks of corn — I consider sweet corn on the cob one of this planet’s great gourmet delights. I’ll admit, I was a little hurt…maybe similar to how Fran felt when I balked at his acorn.

Then I thought about the castañas that vendors had just started roasting in rusted metal bins on the sidewalks of Salamanca. Back home we call them “buckeyes” and slap them on football helmets. It would never occur to me to try eating one. But here, castañas are the roasted chestnuts of Christmas-carol fame…filling the air with a pungent seasonal aroma. And, unlike that acorn, they’re delicious.

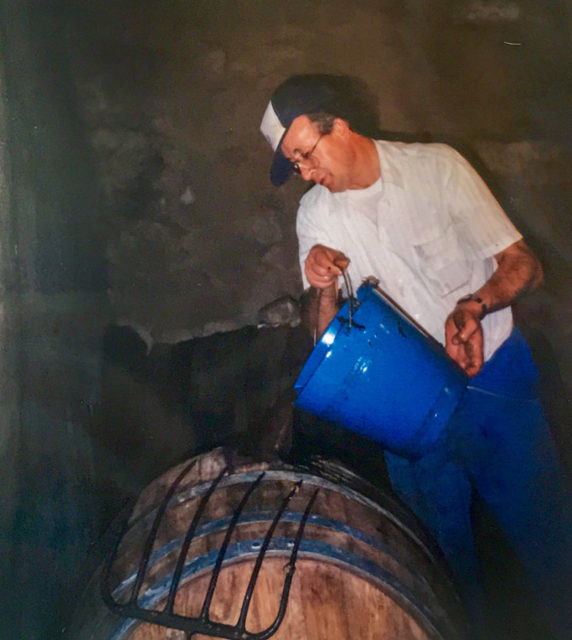

Returning to the farmhouse, my host father announced he was ready for our help with the winemaking. He had pulled on a pair of wine-stained denim overalls and a cockeyed trucker hat. He opened the big, swinging door to a rustic (and, let’s be honest, far from sanitary) barn with a poured-concrete tub in the corner. My host family was far from affluent, but wine in unlabeled bottles always flowed freely at their dinner table. They had told me the wine was casero (“homemade”) — but until now, I had not realized they were the ones who made it.

Fran pulled on a pair of rubber galoshes and climbed into the tub. His father began pouring in buckets of grapes, and Fran squashed them underfoot. Watching my host father make wine — using a method clearly handed down across the generations, relying more on instinct than on science — I suddenly recognized in him the soul of a farmer.

“Moisés, now it’s your turn!” I was hesitant at first, but I pulled on those boots and started stomping. Watching the liquid trickle from the mash of skins and stems out the little concrete spout and into a plastic bucket felt gratifying…productive.

When the bucket was full of mosto (grape juice), Fran’s father lugged it over to an eons-old wooden cask and poured it lovingly into the hole in the top. When all the grapes were stomped, the cask was corked and we headed back to the car. “Now the grape juice ferments,” my host father explained. “We’ll come back next week to check on it.”

Returning home at the end of a long day at la granja, we were in a festive mood. After a light dinner, Fran turned to me and said, “Do you want to do shots?” The question surprised me — it was the first time they’d suggested this (and I’m not much of a drinker). Noticing my puzzled expression, Fran said, “It’s something special. It’s a like a sweet liqueur — but it has no alcohol.” This only made me more confused. “It was a gift from Melanie.” This drew excitement and fond nods from the family around the table. “Sí! Sí! Melanie! Qué buena chica! Melanie was one of our host students, from el estado de Vermont.”

Still not quite sure what kind of sweet, non-alcoholic liqueur I was agreeing to, I watched Fran go to the liquor cabinet and return with a leaf-shaped bottle. “Delicioso,” he promised with a wink, as he opened the bottle and poured the viscous, amber liquid into a few shot glasses. We all picked up our glasses, raised them in a toast, and slugged them down. Lifting the glass, a familiar sensation filled my mouth: maple syrup.

“Uf! Me repite,” Fran said, wheezing and burping a little after his shot — as if he’d just slammed a slug of aguardiente. I stifled a laugh, then started to gently explain that people don’t usually drink maple syrup straight. But quickly, I realized that it doesn’t matter what Americans do with maple syrup. My Spanish family’s improvised custom brought them great joy. Who was I to tell them they were wrong? (And how could I even begin to explain what a pancake is?)

Going to a place where people eat acorns, only animals eat corn-on-the-cob, and a family celebrates with shots of maple syrup challenged my preconceptions about the world I live in. And today, more than two decades later, I realize how I was shaped by those lessons walking with Fran through la granja.

What did I find when I went back to Salamanca so many years later? Read my report on that visit, and on other parts of Spain. Spoiler alert: I must have enjoyed Salamanca, since I included it in my 10 European Discoveries for 2019.

For more on Spanish cuisine, check out my tapas tips for novices and join me on a memorable tapas crawl through Madrid.

If you’re heading to Salamanca, pick up our Rick Steves Spain guidebook, which includes several new restaurants gleaned on my recent research trip.

What are your favorite study abroad memories?

Ahhhhh, Salamanca! Such a beautiful place! I have similar memories of Salamanca—as a college student way back in 1979, the first European city I visited was Salamanca. I was a very green traveler from a small town in Oklahoma, I had barely ever been out of the state. Luckily, through connections at the university I was attending, I had a young family willing to take me in for a while to help me acclimate to a very different place with a very different language. Their apartment was small, in the middle of the city. they had two very young children. Nevertheless, they happily shared their unending hospitality and in several days, I was prepared enough to head out on a wonderful 5 month self-directed tour of Europe. I re-visited in 2006 and it was as if I had never left. Salamanca will always be special to me.

I look forward with great anticipation to reading your upcoming blogs from Spain.

Enjoyed this immensely! Travel writing is my favorite and this was informative, personal, and delightful❤❤

What a wonderful story.

In college, I did an intensive study abroad in Salamanca. We were only there one month, but I fell in love with that city. When I see photos of La Plaza, I close my eyes and transport myself back to that beautiful square on a lively night – chatting with fellow students and eating ice cream. I dream of going back someday very soon.

I loved reading about how “Cameron” might sounds like “camarón” in Spanish, it reminds me of my cousin Penny. When she was in Spain, she went by “Pilar” (for obvious reasons).

Cameron, I love your blog posts. I did not study abroad but in my travels, I have had similar experiences. You write beautifully about them. Please keep those posts coming.

Cameron,

Delightful story! I wish I had had the opportunity to study abroad, your personal account allows me to live vicariously through you.

This story was wonderful. It brought back memories of my year studying in Madrid but it was 1969 and Generalissimo Franco was running the country. The Spanish people were very welcoming but life in Spain was so different from the life I knew in the United States. It really shook up my ideas of politiics and the world at large. So grateful I had this experience that helped form my view of the world.