In our Rick Steves’ European Christmas book (a companion book to the public television show), we outlined the history and many European variations on Santa Claus. Here’s an excerpt:

In our Rick Steves’ European Christmas book (a companion book to the public television show), we outlined the history and many European variations on Santa Claus. Here’s an excerpt:

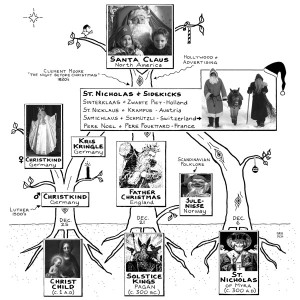

Our American Santa Claus — a plump, jolly old fellow dressed in red — is just one of many gift-giving characters who preside over the Christmas season. Depending on where you are in Europe, it’s possible to bump into St. Nicholas, Father Christmas, Père Noël, Samichlaus, Sinterklaas, and others. All are brothers of sorts, tracing their lineage back either to an early Christian saint or a pagan deity. The origin of these multicultural gift-givers is a tangle of folklore, crossed with some early Christian public relations and a dash of modern commercial branding.

Let’s start with the branch of the family that hails from the frozen north. Long before the birth of Christ, there was Odin, father of the Viking gods. Like Santa, Odin was a stout old man dressed in furs with white hair and a long beard. During the winter solstice, Odin rode through the sky on his eight-legged magical horse, Sleipnir, and descended to earth. Disguised in a hooded cloak, he would eavesdrop on Vikings sitting around the campfire, trying to figure out who had been naughty and who had been nice. Occasionally, he would leave a gift of bread for a poor family.

Around the same time in the British Isles, chilly Celts were crowning a Frost King and appealing for leniency during the harsh midwinter months. In the Middle Ages, the legends of King Frost and Odin became associated with the Christian practice of helping the poor at Christmas. Parishes would hire actors in disguise to go undercover through the village, finding needy families, and reporting back to the village priest. In the 16th century, during the party-hearty reign of the Tudors, the character morphed into Captain Christmas, a sort of master of ceremonies presiding over the unruly fun at Christmastide. Banned by Puritan prudes in the 17th century, he re-emerged in the 18th century in plays put on by itinerant players as Father Christmas.

In the 19th-century Victorian era, Father Christmas was portrayed as a bearded pagan wearing robes and a crown of holly, ivy, or icicles, while hoisting a bowl of wassail. Gone were any saintly attributes, but he was a jolly enough fellow who made people happy during the dark days of winter.

Toward the end of the 19th century, Father Christmas was reinvented as the bringer of gifts to children. This probably came about because of the Victorians’ emerging interest in their children, coupled with influences from Europe and America, where St. Nicholas and Santa were popular.

Today, Father Christmas is a kind old gentleman who dresses, depending on his whim, in a long red robe trimmed with fur or a belted red jacket and cap (in which case he is easily confused with Santa, whose nocturnal habits he has also acquired).

Meanwhile, another branch of the Santa Family tree was sprouting from an early Christian monk named St. Nicholas. It’s believed that the historical Nicholas was born in the Eastern Roman Empire (now Turkey) sometime around A.D. 280. Some folklore experts have suggested his life story was probably recycled from tales of various pagan gods and then Christianized. Legends abound about St. Nicholas, who became the bishop of Myra (modern-day Damre, Turkey) and was much admired for his piety and kindness. He was rumored to have given away all of his inherited wealth to travel the countryside helping the poor and sick. He kept an especially watchful eye on orphans, occasionally giving them gifts; over the years, his reputation grew as a compassionate protector of children.

According to one story, he prevented three poor sisters from being sold into prostitution by their destitute father. Nicholas provided them with a dowry, so they could be married. The legend grew that he gave the money anonymously by tossing bags of gold through a window, or perhaps down the chimney. The gold landed in the girls’ stockings (some versions swap stockings for shoes), which had been left by the fire to dry.

By the Middle Ages, St. Nicholas was the most popular saint in Europe. On the eve of his Feast Day, December 6th (the anniversary of his death), a bearded, robed man appeared in every village, passing out gifts to children and the poor.

In many lands, there were now two Christmas figures — the Christian St. Nicholas (commemorated on December 5th and 6th) and the pagan party animal who became Father Christmas (December 24th, 25th, and beyond). Over the centuries, different cultures merged these two figures, some emphasizing one legend over the other, some celebrating on the 6th, some on the 25th, some both. Today, a European Christmas brings the whole extended Santa Family together as you can see in our chart of Santa’s Family Tree.

Early American settlers had strong ties with the Christmas traditions of England. In the 17th century, Dutch immigrants brought the story of St. Nicholas to America. Americans loved the custom, but had trouble pronouncing the name. The Dutch “Sinterklaas” became “Santa Claus,” and the name stuck. Our modern Santa Claus is an amalgam of European traditions, combining the kindly, gift-giving St. Nicholas and the mischievous, fun-loving Father Christmas.

Today’s image of the American Santa Claus — the jolly fellow with the apple cheeks and twinkling eyes — came by way of a German immigrant who published his illustrations in Harper’s Weekly in the late 1800s. This magnanimous Santa Claus was a boon to shopkeepers during a period of unprecedented growth in retailing — department stores, chain stores, and new-fangled billboards. They joyfully exploited the commercial potential of an entire season dedicated to gift giving, brought to you by Santa. In the 1930s, the Coca Cola Company, in need of a sales boost, borrowed Santa’s image and branded their product with the merry ol’ gent… thus completing his epic journey from saint to salesman.

Today, in many parts of Europe, there’s a movement to preserve the tradition of St. Nicholas, who’s at risk of being crowded out by the American Santa. Some villages are even creating Santa-free zones. They see Santa as a super-size symbol of consumption. St. Nicholas, they argue, embodies the real Christmas spirit, a monk whose example taught that giving doesn’t make us poorer — it makes us richer.